Updated March 28, 2025

Copyright 2012-2025 Susan Burneson. All rights reserved. Please talk with us before reproducing any website content.

The second in a three-part series, in which we introduce a some neighbors-in-history. (See links for more information.)

A number of African American families lived in our area in the 1800s and early 1900s. A 1928 city plan established a “Negro district” in East Austin, and many, but not all, African Americans moved there. Segregation throughout Austin lasted for decades. When Crestview was established in 1947, for example, deed restrictions limited residents to white only; it was not the only Austin neighborhood, park, or business with such restrictions. (Harry Akin, owner of the Nighthawk chain of restaurants, including the Frisco Shop formerly on Burnet Road, was among the first Austin businesspeople to desegregate his restaurants in the late 1950s.)

See the related article by the Austin American-Statesman’s Michael Barnes (may have a paywall): “What you don’t know about East Austin,” May 2016

HANCOCK • WICKS

Rubin Hancock (about 1835-1916) was an African-American enslaved person (and likely a half-brother, according to at least one source) of Austin Judge John Hancock (more about him here). Rubin—and likely other members of his family, including brothers Orange, Salem, and Peyton—lived for a time on what is today the historic Moore-Hancock Farmstead, at 4811 Sinclair Avenue in today’s Rosedale neighborhood of Austin. After they were freed from slavery, Rubin and his wife Elizabeth purchased land near the intersection of Mopac and Parmer Lane in Austin. Rubin and his family were members of St. Paul Baptist Church in Austin, established in 1873, and Rubin served as a deacon there (more about the church and its cemetery, below.)

After Slavery: The Rubin Hancock Farmstead, 1880-1916, Travis County, Texas, is an excellent in-depth report about Rubin and his family, before and after emancipation from slavery.

Interestingly, John Hancock, who was white, is the second-great-grandfather of actress Aisha Tyler, who is African American. The life of Aisha’s great-grandfather and John’s son, Hugh Hancock, was detailed in the genealogy television program “Who Do You Think You Are?” which aired April 3, 2016.

Karen Collins, owner of the Moore-Hancock Farmstead with her husband, Michael, shares much more about the Hancock family and the history of the Rosedale neighborhood in Austin, where the farmstead is located, in her Rosedale Rambles:

1993 • 1994 • 1995 • 1996 • 1997 • 1998 • 1999

In 1992, Karen and Michael received a Texas Historic Marker for the Moore-Hancock Farmstead from the Texas Historical Commission. You can read the application they submitted here. Michael, an archaelogist, and Karen are featured in the film The Stones Are Speaking, about Michael’s work on the Gault Site near Florence, Williamson County, Texas. Beginning March 2025, the film is airing on PBS.

In the late 1930s, Emma Hancock Wicks, Orange Hancock’s daughter and Rubin Hancock’s niece, was interviewed during the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), later renamed the Works Projects Administration. A transcript of Emma’s interview is now part of the WPA Texas Slave Narratives; one version is here.

Note: In the Slave Narratives, Emma’s last name is listed as “Weeks.” Emma’s descendant Murray M. Myers sent the correct spelling, “Wicks,” in a 1/23/21 email to Susan Burneson. According to Texas marriage records, Emma Hancock married Elzah Wicks in Travis County, Texas, in 1891. Both their death certificates show that their last name was Wicks, and his first name was listed as Elijah. Also, Emma’s death certificate lists Owens Hancock as her father. This is incorrect. According to public records, Owens, the son of Thomas and Frances Eggleston Hancock, never married and had no children.

See the related article by the Austin American-Statesman’s Michael Barnes (may have a paywall): “A US Congressman, his enslaved half-brothers and the history of an Austin log farmstead,” February 2025

ST. PAUL BAPTIST CHURCH AND CEMETERY

The original location of the African-American St. Paul Baptist Church, established in 1873, was north of today’s Ohlen Road between Burnet Road and Highway 183. In 1951, the church moved to a new location not far away, where it remains active today. A number of Hancocks and their relatives are buried in the St. Paul Baptist Church Cemetery, a few miles west. According to several sources in the report After Slavery (see above), Rubin Hancock and his wife Elizabeth also are buried there. Limited records of burials and related death certificates and photographs can be found on the St. Paul Cemetery page on findagrave.com (scroll down on the page to see all recorded burials at St. Paul).

Note: The church’s website shows its name as “St. Paul.” On Find a Grave, the cemetery is listed as “St. Pauls.” The sign on the cemetery fence reads “St. Paul’s Baptist Church.”

In the early 2000s, I first learned of the cemetery from Susan Kathleen Kirk, whose maiden name is Arbuckle. She grew up on Morrow Street in Crestview in the 1950s. As a teenager she took long walks north of Anderson Lane, then mostly farmland, and discovered the remnants of what she believed was an African American cemetery in an open field. Today, it is fenced and continues to be maintained by church members. It is surrounded by homes in the Wooten neighborhood, north of Anderson Lane between Burnet and North Lamar.

Leslie Wolfenden, Historic Resources Survey Coordinator for the Texas Historical Commission as of September 2023, included St. Paul Baptist Church cemetery, among others, in her 2003 master’s thesis, Austin’s Cemeteries: State of Preservation and Their Futures, pages 119-120. Her research included walking the cemetery and making detailed notes about what she found there, including names, dates, and condition of the markers and grounds. (She generously shared a copy of her notes with Susan Burneson in 2009.) Leslie’s thesis can be found at the University of Texas at Austin.

According to the Travis County Historical Commission, the 1906-1907 Travis County School Annual mentions two African American schools in Fiskville District No. 11 (then located about eight miles north of Austin)—St. Paul School, possibly connected to the church and cemetery, and Walnut Creek. It states, “Walnut Creek and St. Paul should be consolidated. There is absolutely no sense in maintaining the two schools, in the same district, so close together, on $200 a year, $100 to each school.”

DOXEY

Hattie Doxey (1849-1924) also is buried in St. Paul Cemetery, according to her death certificate. Likely other members of her family are buried there, too. Hattie was the first wife of Spencer Doxey (1840-1902), listed in property records as a “colored man.” Spencer likely was enslaved by James Daugherty Doxey. According to an oral history of his grandson Thomas Adams Doxey Jr. at the Austin History Center, James came to Texas from Missouri in the 1850s and later brought his three sisters and three enslaved people, including a man closely matching Spencer’s age. James Doxey served as a Confederate soldier in the Texas Cavalry in the Civil War.

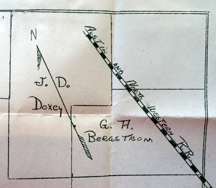

In 1871, James Doxey purchased property in what is now the northern section of Crestview (left). He sold land in the northeast corner of his property to his former slave Spencer Doxey in 1874, 1881, and 1885, according to property abstracts of the area. In 1881, the Austin and Northwestern Railroad Company purchased 30 acres of Spencer’s property, so that rail lines could be constructed through that part of today’s Crestview. (More about the railroad here.) Spencer could not read or write, so he indicated his signature with an “x” on the legal transactions that became part of the property’s abstract of title. In public records, his last name is spelled “Doxie,” “Docksey,” and “Docksie.” The abstract also includes maps, including the one, left, showing James Doxey’s land and the location of the railroad. (More about property abstracts, as told by former Brentwood neighbor Al Kirby.)

In 1871, James Doxey purchased property in what is now the northern section of Crestview (left). He sold land in the northeast corner of his property to his former slave Spencer Doxey in 1874, 1881, and 1885, according to property abstracts of the area. In 1881, the Austin and Northwestern Railroad Company purchased 30 acres of Spencer’s property, so that rail lines could be constructed through that part of today’s Crestview. (More about the railroad here.) Spencer could not read or write, so he indicated his signature with an “x” on the legal transactions that became part of the property’s abstract of title. In public records, his last name is spelled “Doxie,” “Docksey,” and “Docksie.” The abstract also includes maps, including the one, left, showing James Doxey’s land and the location of the railroad. (More about property abstracts, as told by former Brentwood neighbor Al Kirby.)

In the 1870 U. S. Census for Travis County, Spencer Doxey is listed with his first wife Harriet (nee Faicklin) and daughter Mary. He was a field laborer. They lived near John Hancock’s former enslaved persons (and likely half-brothers) Orange, Peyton, and Salem Hancock. In the 1880 census, Spencer lived with Hattie (short for Harriet), and daughter Mary. By then he was a free man who owned his own property, and he listed his occupation as farmer. He married Mary Meeks in 1884 and had nine children with her, before he died in 1902. He and his second wife, Mary, are buried in Brown Cemetery, Manor, Texas.

DELONEY

A 1932 survey of the North Gate Addition (excerpt below, click to enlarge) indicates that Mary Green Deloney, an African-American woman and a widow, owned property just west of the addition. Her land included the east side of today’s Tisdale Lane in the northeast corner of the Crestview neighborhood. Mary was born December 9, 1886, in Washington County, Texas, the daughter of Henry and Elvira Blackshear Green.

North Gate Addition is south of Anderson Lane (then known as County Road), north of Aggie Lane, west of North Lamar (then known as State Highway No. 2 and Lower Georgetown Road), and includes homes on the west side of Gault. Mary’s property was just east of property owned by Spencer Doxey (described above).

North Gate Addition is south of Anderson Lane (then known as County Road), north of Aggie Lane, west of North Lamar (then known as State Highway No. 2 and Lower Georgetown Road), and includes homes on the west side of Gault. Mary’s property was just east of property owned by Spencer Doxey (described above).

In 1920, Mary lived in Pflugerville, Texas, with her husband, John Deloney, and four daughters—Alberta (who married Walter Spence), Bessie Lee, Elanora, and Alma. John, a farmer, died in 1929. In the 1930 census, Mary was a widow, farmer, and head of household, living with five daughters near Lower Georgetown Road (today’s North Lamar). During 1934-1935, Mary’s daughter L. V. reportedly attended Fiskville School.

More about Austin’s African American rural schools here. Note: Not all of the information in this report is correct, including the listing of Esperanza School as a rural school for African-American students. Esperanza was located in what later became the Brentwood neighborhood of Austin. Based on other documents, detailed on the Esperanza School page, only white students attended the school.

At the time of the 1940 census, Mary Deloney’s address was Tisdale Lane, which runs roughly north and south, east of the railroad and west of Lamar. Today, Tisdale is part of the Crestview and Wooten neighborhoods. Mary was listed as the head of household, living with three daughters, a grandson, and a son-in-law. Her daughter Alberta Spence and family lived next door. Mary died in 1943. The Crestview neighborhood began to be developed in 1947 and was designated a “white” neighborhood at the time. In 1950, Alberta Deloney Spence and her family lived on Bennett Avenue, east of IH-35 in the St. Johns area. Alberta died in 1963.

John Deloney (about 1885-1929); Mary Deloney (1886-1943); their daughter Alberta Deloney Spence (1905-1963); and Alberta’s husband Walter James Spence Sr. (1900-1983), daughter Novella Spence Lee (1930-2001), and son Walter James Spence Jr. (1933-1994) are buried in Burditt Prairie Cemetery, Travis County, Texas. Burditt’s Prairie was one of Austin’s original Freedmen Communities established after the Civil War. (Note: John and Mary Green Deloney are listed on their death certificates as buried in Burditt Prairie Cemetery, although their names are not listed as buried there on findagrave.com.)

A BIT MORE HISTORY FOR CONTEXT

About mid-way through the Civil War, on January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order stating that all enslaved people in Confederate territories, including Texas, were forever free. It was not enforced in Texas until June 19, 1865—two months after the end of the Civil War. Today, June 19 is celebrated in 41 states as Juneteenth, the oldest known celebration marking the end of slavery.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution—the subject of Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln—made slavery illegal everywhere in the United States; it took effect on December 6, 1865. The challenges of the Reconstruction period following the war (1865-1877) and Jim Crow laws that lasted until the 1960s limited the rights of African Americans, despite the thirteenth, fourteenth (1868), and fifteenth (1870) amendments. (Read more about these amendments here.)

Read “Neighbors-in-History, Part 3,” here.